| ABOUT THE WARRIORS The Story of the Warriors is a story as old as art and older than human civilization as we usually define it. At the beginning of the new Millennium the legendary figurative artist Trevor Southey, spent a month in Russia starting a body of work exploring war, with all of its complexities, intrigues, innocent death, and horror. Avoiding the obvious and combining his fertile imagination with extraordinary technical skills, Southey has created a body of work with a wide eternal message to mankind that manages to be approachable on a broadly human yet individual level. Southey‘s veiw envelopes the whole human family using his Russian experience as a catalyst. He manages to probe the universal yet retains a very personal touch. His Warriors subtly, almost ironically exposes the reality of conflict, war, and death thru the eyes of the most vulnerable and directly affected. The Warrior collection brings to the forefront a brilliant figurative artist of immense talent. Trevor Southey is an artist who combines a vision that is timeless yet contemporary with the raw instinct and trained ability to paint the human form rarely matched in the twentieth century. Remarkably, Southey does this across all media. He is equally adept at drawing, printmaking, painting and sculpture. His Warrior series in all of its media forms is a watershed in figurative, realistic art in our time. James Dabakis |

||||

| FROM THE ARTIST He was 20. To respect his privacy we only used his first name, Vladimir, or more casually, Vova. We could not really communicate much. My few words of Russian were barely bettered by his few words of English. Perhaps over the years of my African childhood and youth, plus years of other travel, a capacity grew in me to get through to others by gesture and a few stick figure sketches, for I was able to glean quite a bit about him. Later, an electronic interpreter inadequately assisted us. |

||||

Aleksei | Sevastopol, Crimea |

He was one of many young men who came to a party with the idea that they may be selected for this project. They may simply have come for the five dollars each was given, but they were also full of youthful curiosity; clearly eager, shy, excited, amused, or any combination thereof, politely trying to make a link to us as they exchanged repartee with each other. There were three such parties over three different trips to St. Petersburg. Because most were so keen, it was excruciating to make choices. Those selected later posed for drawings and also some intensive photography to be used as resource material for the final paintings. Vova came from a very small village deep in the country beyond Novgorod. He did not mention his father; presumably dead or otherwise gone, but did show me a few pictures of his mother and their humble, wooden cottage. His mother currently attends eighty calves at a farm near her village. Because she was at work all the time, his Babushka (grandmother) had largely raised him. I commented that he seemed like a real gentleman and teased him that perhaps she had had to chide him often to make him such a gentleman. Indignantly he entered a word in the interpreter that translated into "never!" His demeanor added the exclamation mark. One could tell he must have always been a serious boy. |

|||

| But the real communication came as we worked over a period of nearly three hours. I located him close to the easel and asked that he watch my eyes. I became aware that a remarkable communion was occurring. This was much more potent than it might have been if the clutter of language and thus culture had intervened. It even bridged the generation gap. It was as if there was an exchange of something, some ingredient between us, human to human, that profoundly connected us. Sometimes it made us nervous. At times he would suddenly smile, and then at others giggle with a kind of delight. My added years yielded some insight, but we both seemed to comprehend something extraordinary. We might try to speak every now and then but it added little. Even now so many months later, I feel an elusive connection with him and with most of the others. |

||||

| When I gave him a rest, he would abruptly become a callow youth again, grab a cigarette and then linger bemused over the evolving drawing, smiling or glowering his opinion. There was a new essence there now. It seemed as if this time of communion had awakened not only my perception of his deeper human dimensions, but also his own. Of course one could easily be deluded into thinking this might have lifelong ramifications, but more likely the encounter would be lost in the general hubbub of life which consumes us all. One could only hope that memory would bring this time back and enrich it again. Perhaps the experience would be used as a guide in future silent communion with others. They could be seen all over St. Petersburg, double lines of boys and young men in a variety of uniforms walking to and fro about their academies, soldiers and sailors. At other times small groups or individuals would pass by or could be seen smoking and chatting. |

detail Maxim detail Maxim |

|||

| We have been compelling them into battle since before the beginning of human history, these boys, these lads often barely bearded. Uniforms make uniform the parade, and insignificant the individual. The romance and excitement are enhanced by glittering braid, coloured ribbon and big brass band. They go marching off to glorious battle, to the passionate cries of proud families and countrymen, full of national union and righteous intent. Most often the glory evaporates as bodies are shattered, uniforms become soaked in blood, so that one cannot be quickly distinguished from another, enemies united at last, unified ultimately by red. |

||||

Pavel | St. Petersburg, Russia Pavel | St. Petersburg, Russia |

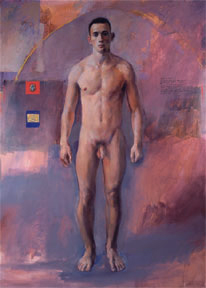

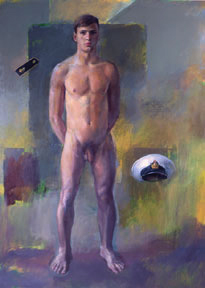

All over the world there are acres of neat graves of these young, often preserved with suitable reverence but rarely remembered by the new generation. And then there are the walking dead, victims or perpetrators, bodies and/or minds warped and twisted by the inevitable atrocities. They are lost among us, often an embarrassment because they make us feel responsible. The names of the wars and battles are legion. The reasons are plenty and rarely justified: religion, nationalism, avarice, ancient hatreds, ego, and once in a while the clear madness of some person charismatic enough to charm a nation. Nude, they cease to be Russians. The nudity is deliberately also chosen to suggest the sheer vulnerability of these specific people, their human being, their connection to ourselves... indeed their likeness to us, which so easily becomes hidden under the lie of the uniform making them anonymous and that much easier to kill. |

|||

| It would be silly to disavow the reality of some, if inadvertent, erotic component to these works. That is a potent part of our human nature. But most importantly, these boys/men are the children and grandchildren of parents and grandparents in Russia, though they could just as easily have been American, Korean or Iraqi. We partially kill these parents and grandparents in a way each time we kill a soldier, sailor or airman. I knew too well the “dying” my own grandmother endured as she lived with the death of a son shot down over Holland in World War II. Another son, also shot down, endured the living death of a life shattered by the appalling memories of being a prisoner of war, of forced marches and before his eyes the summary execution of others, including his best friend, because they were too weak to march any more. |

||||

Of course, there is little likelihood we will be able to send all these young back to the bosoms of their families and close up military shop for generations. The horror of September 11, 2001 is just another reminder. The seeds of war are sown too deep. Trevor Southey |

detail of Yuri |

|||

| Note: This project is the brainchild of my old friend and collector Jim Dabakis. Since 1982 he has been traveling to Russia, falling in love with its people and dreaming of honoring them in some way. My expression of peace grew from his simple idea of recording the faces of some of these people. Twenty-two drawings, a couple of oil sketches and innumerable photographic records created over three trips to Russia were the beginning. They have seeded twelve life-size, full figure paintings. Each is portrayed with fragments of uniforms and other military accoutrements surrounding their naked bodies. A brief biographical note written in his own hand is silk-screened to the canvas. |

||||

| back to top | ||||